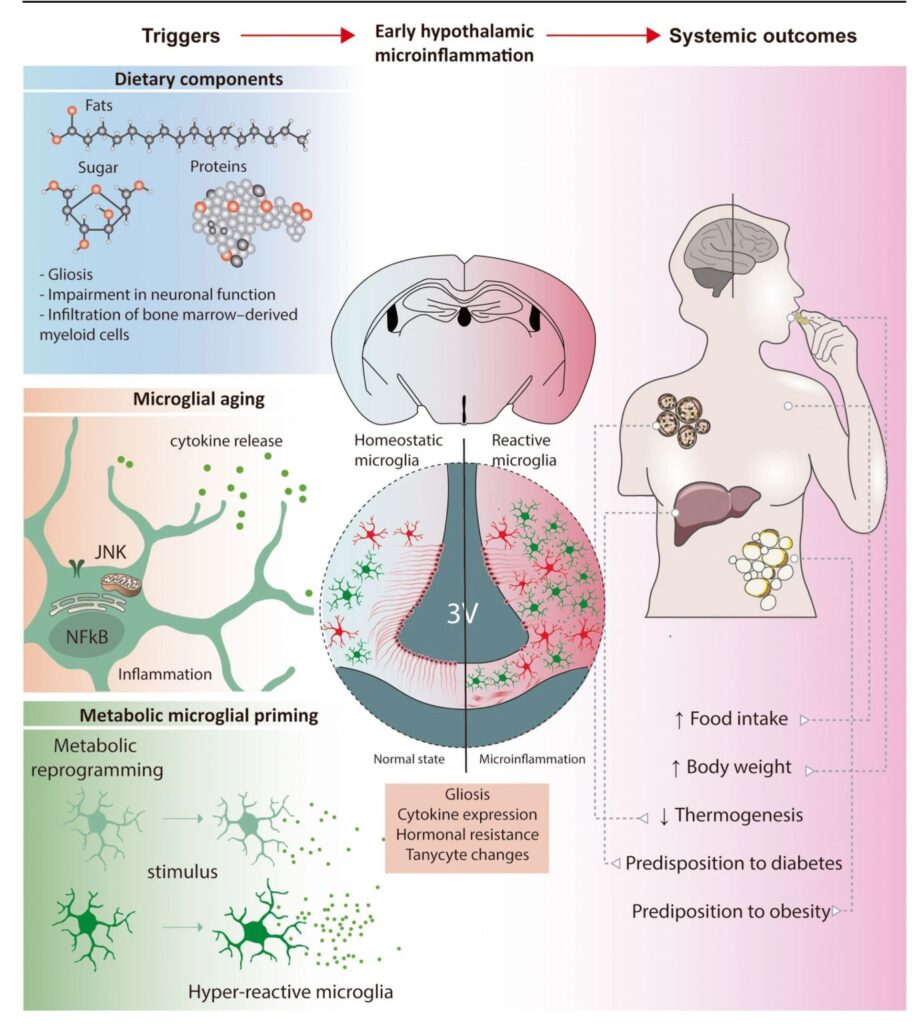

A new review by Sebastián Zagmutt Caroca et al positions chronic hypothalamic microinflammation as an initiating event, not a downstream consequence, of systemic metabolic dysfunction and obesity: “The hypothalamus plays a central role in regulating energy balance, and its dysfunction is a key contributor to the development of metabolic diseases such as obesity and type 2 diabetes… Hypothalamic microinflammation is triggered by various metabolic stressors, including high-fat diets, aging, and glial priming, and occurs even before peripheral tissues show signs of inflammation. ” https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11154-025-09992-3

In their review they propose three distinct phases of hypothalamic inflammation: the Initiation Spark, characterized by rapid inflammatory signaling; the Adaptive Transition, where compensatory mechanisms attempt to restore homeostasis; and the Dysfunctional Phase, leading to chronic inflammation and metabolic dysfunction.

The inflammatory response is modulated by diet composition, aging, and microglial priming, and exhibits marked sexual dimorphism.

If confirmed, this could redefine therapeutic strategies for metabolic disease—targeting the inflamed hypothalamus as the origin rather than the consequence of systemic dysfunction.

As discussed earlier, the brain is undoubtedly a key missing organ in current clinical frameworks of obesity https://www.yulialurye.com/mental-health-role-in-obesity-management/

Moreover, brain health and mental health should be considered separately. If food can alter brain function and induce hypothalamic inflammation—as demonstrated in this article—then, in cases where mental health is the primary driver, food may be the last factor to blame.

My only hesitation in accepting the hypothesis that obesity is a downstream effect of hypothalamic inflammation lies in the fact that, in metabolically healthy individuals, a normally functioning digestive system, a non-steatotic liver, nutrient-sensitive pancreas and intestine, insulin-sensitive adipose tissue, should mitigate, at least to some extent (though not completely), the negative effects of an unhealthy diet, until their compensatory capacity fails.

From the perspective of organ vulnerability obesity may be heterogeneous in terms of which organ becomes the first “weak link” in the chain of events that form vicious cycles. It could be the hypothalamus, the liver, the heart, the pancreas, the intestine.

Attempts to develop single organ-centric model of obesity remain valuable, as they help identify root causes at the individual level and may inform preventive or early-intervention strategies. However, with the advent of NuSH therapies that offer pleiotropic effects, a multi-organ or systemic approach may prove more practical.

Below are a few publications that discuss the “protective” potential of a healthy liver, pancreas, and adipose tissue. These findings do not contradict the current research on neuroinflammation but rather complement it:

– Neumann HF et al. (2021) — Impact of meal fatty acid composition on postprandial lipemia (systematic review / trials). “In metabolically healthy adults, the fatty acid composition of a meal is not a relevant determinant of postprandial lipemia.”

– Velenosi TJ et al. (2022) — Postprandial plasma lipidomics: hepatic secretion changes in NAFLD.

– Matikainen et al., Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism (2007) — – Postprandial lipemia associates with liver fat content.

– Carpentier AC (2020) — 100th Anniversary of the Discovery of Insulin Perspective: Insulin and Adipose Tissue Fatty Acid Metabolism. Pancreatic β-cell function and insulin sensitivity determine lipid handling.

– Risi R. et al. (2024) — Adipocentric Perspective of Pancreatic Lipotoxicity (Review). “The adipose tissue (AT) expandability hypothesis explains that the individual capacity to appropriately store energy surplus as fat within the AT prevents the toxic deposition of lipids in other organs, such as the pancreas.”

Looping back to the role of the brain in obesity, I would move one level higher in the cascade of downstream effects – to the central regulation of hedonic appetite and the wiring of the reward system, overexpressed obesogenic genes within the CNS, and the role of ultra-processed food in rewiring appetite regulation.

Leave a Reply